As we approach the halfway mark of the year, it appears that 2016 will be a very strong year for the controversial asset class known as gold or, more broadly, precious metals. What with Brexit, negative interest rates, and continued money printing by the world’s central banks, it seems that the yellow metal has finally emerged from being in the doldrums for three years. The five-year high of US$1,901/ounce occurred some four years ago, sinking to a low of US$1,052.70 in the past year. But bullion has been on a tear this year and is currently just under US$1,300.

Where from here?

Traditionally, The Motley Fool has been—at best—agnostic about gold, if not outright bearish, on the grounds it has no intrinsic value and that it pays no yield (unless it’s a senior gold stock). I presume the general perception here is that gold “bugs” constitute the lunatic fringe of investing.

I certainly understand that perspective, but I personally have long believed in holding about 10% of my total portfolio in some combination of gold bullion ETFs (like SPDR Gold Trust ETF (NYSE:GLD)), precious metals equity mutual funds or ETFs, individual blue-chip gold miners, and even a tiny bit of coins or bullion to tuck away in a safety deposit box. Even a stock junkie like Mad Money’s Jim Cramer has a standing recommendation to hold 10% in this asset class as a form of “insurance” against utter financial and economic crisis.

In a world of “fiat” electronic and paper money, real money (that is, gold or silver coins or bullion) could be the ultimate uncorrelated asset should the whole house of paper-money cards come tumbling down after decades of currency debasement by the U.S. Federal Reserve and its global cousins.

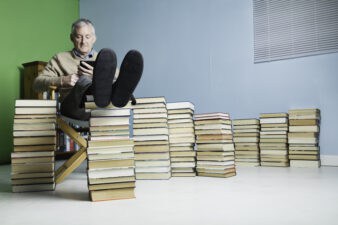

To that end, I refer readers to a couple of recent books that go into this theme in far more depth than this article can. One is The New Case for Gold by James Rickards, which I read on my Kindle while holidaying recently in Florida. Keep in mind Rickards’s previous books, whose subtitles I include here because they tell you exactly where he’s coming from: The Death of Money: The Coming Collapse of the International Monetary System and Currency Wars: The Making of the Next Global Crisis.

Far out stuff, I agree, and I sympathize if that’s as much about this topic as you wish to absorb; in which case, see you next month.

The “new” case

If you’re still here, what exactly does Rickards mean by the NEW case for gold? Rickards does go beyond the familiar arguments of gold as a combined inflation/deflation hedge and does so in a 21st-century context. He breaks new ground by referring to gold’s role in cyberfinancial warfare, its importance in economic sanctions in nations like Iran, and gold’s future as a competitor to the world money system known as SDRs, the Special Drawing Rights issued by the International Monetary Fund.

Rickards’s main thesis is that G-Day is rapidly approaching—an ominous day when all of the investors with mere paper or electronic claims on bullion actually attempt to procure the actual physical underlying metal. Like a run on the bank, the claims would far exceed the actual amount of the available metal. If and when that occurs, he believes the price of the metal would soar to over US$10,000/ounce, in which case even a 10% insurance position would nicely cover losses in other asset classes should such a global monetary collapse actually occur.

The other book I read on holiday (What can I say? I have no life!) is the new updated 2016 edition of Peter Schiff’s The Real Crash. Like Rickards, Schiff is bearish on the U.S. dollar and the viability of the U.S. government. In a nutshell, he believes Uncle Sam is broke and living on borrowed time. Actually, investors can ignore most of the book and its political recommendations and skip right to the final chapter, titled “Investing for the Crash,” in which he asserts that what investors thought was safe is no longer safe: chiefly the U.S. dollar and U.S. Treasuries.

In a nutshell, Schiff splits his recommendations into three equal chunks: foreign (not U.S.), quality dividend-paying stocks (mostly from Europe), cash and foreign bonds; and yes, gold and gold-mining stocks. He likes both physical gold (his firm offers it) as well as a portfolio of senior gold miners and mid-tier and junior producers. Those who don’t want to do the research can use diversified mutual funds, which Schiff’s firm also sells.

Convinced?

In summary, while this Fool doesn’t plan to go overboard on the asset class, I plan to maintain my usual 10% position and hope the gold bugs and bear authors are proved wrong. But on the off chance they’re even half right, this “insurance” position does seem to help me sleep better at night. And isn’t that the whole point about insurance?