If your financial advisor starts to warn you about lower returns from financial markets going forward, don’t be surprised. Advisors at the 2017 Vanguard Investment Symposium in Toronto on Tuesday collectively chose “implications of lower returns” as the number one discussion point.

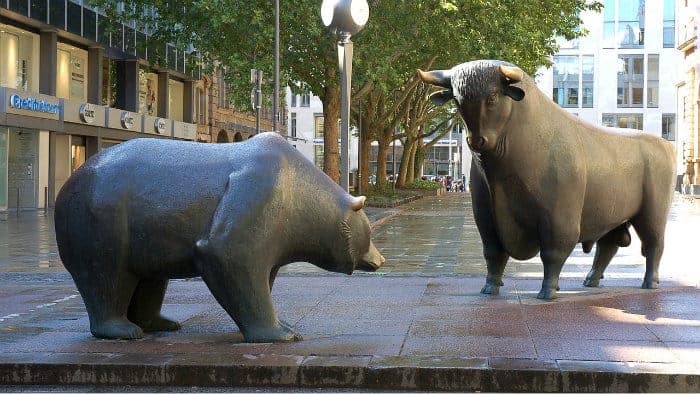

The cautious stance applies to both stocks and bonds. Indexing giant Vanguard Group is not a big believer in investors holding cash right now. But there is one bull market ahead, it predicts: “in advice.”

Gregory Davis, formerly Global Head of Vanguard’s Fixed Income Group and now chief investment officer, said the firm has a “guarded view” of returns given the “global cross-currents of low yields and equity valuations … 10-year expected returns for balanced portfolios [are] lower than historical averages, with shorter-term expectations even lower. The next five years will not look like the last five.”

Actually, global equity returns have been relatively disappointing since 2000. While annualized returns were 8.8% per annum between 1970 and 2016, they’ve been cut in half—to 4%—since the year 2000.

Mind you, the second featured speaker—principal and global head of portfolio construction Fran Kinniry—started by warning that forecasting with precision is “challenging,” even at the best of times. The average annual forecasting error among leading market strategists between 1998 and 2016 was a whopping 13.7 percentage points, and no strategist predicted negative returns in the three years that served up the greatest losses for investors: 2001, 2002, and 2008.

That said, Kinniry showed a chart on global stock outlooks with roughly a 20% chance of 10-year annualized returns between 6% and 9%, a slightly lower probability of returns between 3% and 6%, or 9% to 12%, and still lower probabilities of returns of 0% to 3% or less, or of 12% to 18% or more (a classic Bell curve with decreasing probabilities at the tails).

Meanwhile, the outlook for global bonds over the next 10 years is “somewhat muted,” Davis said. He showed a chart with a 45% probability of a 10-year annualized return of between 1% and 2%, a 30% chance of returns of 0% to 1%, a 15% chance of returns of 2% to 3%, and a miniscule chance of returns of 3% to 4% or more.

When you combine the expected returns of both global stocks and bonds, you can understand the caution about getting retail investors too excited about returns of balanced portfolios. Going forward, these will be “about half the long-term average,” Kinniry said. Even so, despite these disappointing projections for bonds, Vanguard is not telling advisors—and hence their clients—to therefore abandon fixed income. “Bonds provide ballast in an equity bear market,” Davis said.

So, what to do about this low-return environment? A common response by investors (and even some advisors) to low returns is to reach for yield by increasing risk (i.e., raise equity exposure, or in the case of bonds extending duration or moving to high-yield or “junk” bonds.) Vanguard does not advocate departing from balanced portfolios, but prefers bonds over cash.

Another common response to low returns is to lower spending and/or to work longer, Vanguard says. Of course, neither response is likely to endear advisors to their clients. As you might expect from Vanguard, the better path is to reduce costs, taxes, and what it calls the “behaviour gap.”

Investors tend not to rebalance their portfolios at market tops, just when they need to, and are similarly disinclined to enter markets at market lows, which is why Kinniry predicts a “bull market in advice.” He showed slides that quantify the value of advice under Vanguard Advisor’s Alpha strategy: Behavioural coaching is the single biggest value-add: 150 basis points (1.5%). “Staying the course is difficult,” but “a balanced diversified investor has fared relatively well.”

Behavioural coaching is followed closely by 131 beeps for cost-effective product implementation (using low expense ratios). This alone can add one to two percentage points of value, Vanguard says, attributing the finding to “numerous studies.” Rebalancing accounts for another 47 beeps, and Asset Location between 0 and 42 beeps (as opposed to Asset Allocation, which it says adds “more than 0 beeps.”)

A proper spending strategy (identifying the order of withdrawals in the decumulation stage) accounts for another 0 to 41 beeps. All told, the potential value added comes to “about 3%,” Kinniry says.

While time precluded a formal presentation of the future and evolution of the advisory business, Vanguard’s printed materials said a “strong move to fee-based” compensation is accelerating. In 2015, 65% of advisors’ compensation came from asset-based fees, while wealthier investors are “most willing to pay AUM-based fees.” Gradually, this will “flow down” to less well-heeled clients, “as smaller balances can now be well-served” in a fee-based model because of scale and technology.

Using Cerulli data from 2015, Vanguard estimates the median asset-weighted advisory fee is 1.39% for the mass market ($100,000 assets), 1.28% for the middle market ($300,000), 1.09% for the mass-affluent market ($750,000), 0.92% for the affluent market ($1.5 million to $5 million) and 0.70% for the high net worth market ($10 million or more).

On average across all clients, the median fee is 1.07%.