Imagine you’re a new Canadian investor. You’ve got a nest egg saved up and are looking to invest it and generate returns for your retirement portfolio.

You go to the bank and buy into a mutual fund after speaking to a “financial services associate” (a salesperson). You also set up a self-directed brokerage account and invest in some Canadian blue-chip stocks your friends recommend — a bank, a telecom, a railway, a pipeline, etc.

You’re all set now, right? Probably not. It turns out that these common practices could cost you dearly in terms of high fees and missed returns over the years. Let’s dissect them and figure out how beginners can avoid these pitfalls.

High mutual fund fees

The Canadian mutual fund industry charges some of the highest management expense ratios (MER) around the world, with an average of 2-3%. The MER is deducted from the net asset value (NAV) of your fund on a daily basis and calculated annually. For example, if your mutual fund returned 12% gross this year and had a MER of 2%, your net return would actually be 10%.

2% might not seem like a lot to most new investors at first glance. With a $10,000 portfolio, 2% a year amounts to $200. However, over long periods of time, this fee amounts to significant losses in potential gains owing to how compounding returns and the time value of money works.

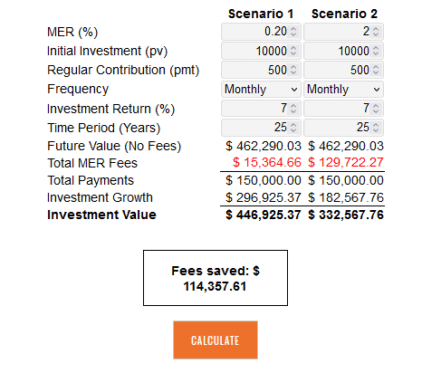

Below, I’ve plugged in a head-to-head comparison of an exchange-traded fund (ETF) versus a mutual fund that both track the same underlying stock index using the MER calculator on the Learning to FI website. Both return the same compound average growth rate (CAGR) of 7% on a pre-expense basis, but the ETF has a lower MER of 0.20% compared to 2.00% for the mutual fund.

The difference is astonishing. With a starting sum of $10,000 and a monthly contribution of $500 over 25 years, the mutual fund would cost you more than six figures in fees and unrealized gains. The power of compounding ensures that 2% takes a significantly bigger chunk out of your portfolio the longer time goes on compared to just 0.20% for the ETF. Minimizing fees is therefore absolutely critical to successful long-term investing.

Too much home-country bias

In investing lingo, a “home-country basis” refers to the phenomenon where investors tend to overweight the proportion of domestic stocks in their portfolio relative to their actual weighting in the total world stock market. For example, while Canadian stocks comprise just 3% of the world stock market capitalization, many Canadian investors devote 50% or more of their portfolio to them!

The reasons for this vary but usually relate to a feeling of familiarity and comfort. Canadian investors psychologically feel more comfortable buying what they are familiar with and feel that they know and understand. They are more willing to make bets on their own economy and think these stock picks will be more transparent and easy to understand. They may own products or use services from these companies on an everyday basis, and thus trust in their reliability and profitability.

The reality is that the Canadian stock market is heavily concentrated in the energy and financial sectors, which causes a Canada-heavy stock portfolio to be severely underdiversified. This exposes investors with a significant home-country bias to concentration risk, where the aforementioned sectors might underperform poorly for years on end. They may also miss out on gains from other countries, such as the 10-year bull run the U.S. S&P 500 has been on.

However, not all home-country bias is bad. Research shows that a moderate weighting of 20-30% to Canadian stocks can help reduce portfolio volatility and currency fluctuation risk for Canadian investors. The rest should comprise a diverse selection from the U.S., European, Asian, and emerging markets around the world. Doing so ensures that you match the market over the long term and minimize the risk of significant under performance.

The Foolish takeaway

Successful investing depends on minimizing the controllable sources of risk in your portfolio. Two common ones incurred by new Canadian investors include high mutual fund fees and excessive home-country bias. Both can cause your portfolio to underperform significantly over the long run.

One way to avoid these problems is to invest in ETFs from fund managers such as Blackrock, Vanguard, and Horizons using any self-directed brokerage. They now offer “all-in-one” diversified portfolios that hold anywhere from 9,000 to over 12,000 worldwide stocks at low management expense ratios (anywhere from 0.20% to 0.25%). Buying and holding one of these funds in a consistent, disciplined manner could put you ahead of most new investors.