I cringe at the thought of new investors buying exotic exchange-traded funds (ETFs). Recently, this includes covered call ETFs, which unsuspecting investors are drawn to because of the high advertised yield, sometimes in excess of 5% or more.

Remember, the markets are efficient. That high yield isn’t free money – it either comes from taking on more risk, or in the case of covered call ETFs, selling your future upside gains for a upfront fee, while still being exposed to the downside of owning a stock.

For most investors and under the majority of market conditions, a simple buy-and-hold strategy with a vanilla ETF will handily outperform its covered call cousin on a total return basis. Confused? Keep reading to find out why.

Image source: Getty Images

How do covered calls work?

A call option is a derivative contract that gives the buyer of the call the right, but not the obligation, to buy 100 shares of a stock at a specific price called the strike. Think of it as an IOU contract for a stock you can buy or sell as a separate instrument.

On the other side, you have the seller (writer) of the call. If the seller of the call owns 100 shares of the stock they sold a call on, that call is said to be covered. If the price of the stock goes above the strike, the buyer can exercise the call, and the seller will have to sell the 100 shares to them at the strike price.

The seller of the call option collects a upfront fee for doing so, called the premium. The amount of that premium differs but tends to be higher when the expiry date of the option is further out, implied volatility is high, and the strike price is close to the current market price, called “at the money”.

Finally, options contracts lose value daily, accelerating as it nears expiry (theta). The buyer of the call has until a specific day to exercise or sell the call. If the price goes above the strike, the option is “in the money,” and has intrinsic value. If not, the option is “out of the money” and only has extrinsic value.

Why covered call ETFs underperform

The premium received from selling the covered call represents the gains the market thinks is fair to assume you’ll make at the time of expiry, based on the strike you sold at. For all intents and purposes, it’s priced in. All in all, covered call strategies tend to only outperform in sideways markets.

In a bull market, the price will blow past your strike and you’ll be assigned. This means you’ll have to sell your shares to the buyer of the call at the strike price, missing out on larger gains if you simply sold at the share price. This can significantly reduce your return during a large rally.

In a bear market, the call you sold will not get exercised, as the share price will be below the strike price (out of the money). In this case, you can keep the premium you received, but your shares will incur a loss, which may be partially offset by the premium.

However, future calls you sell might not reap as large of a premium, as your cost basis is much higher than the current share price, forcing you to sell at lower strikes. Implied volatility usually also drops, which reduces your premiums even more.

What the numbers say

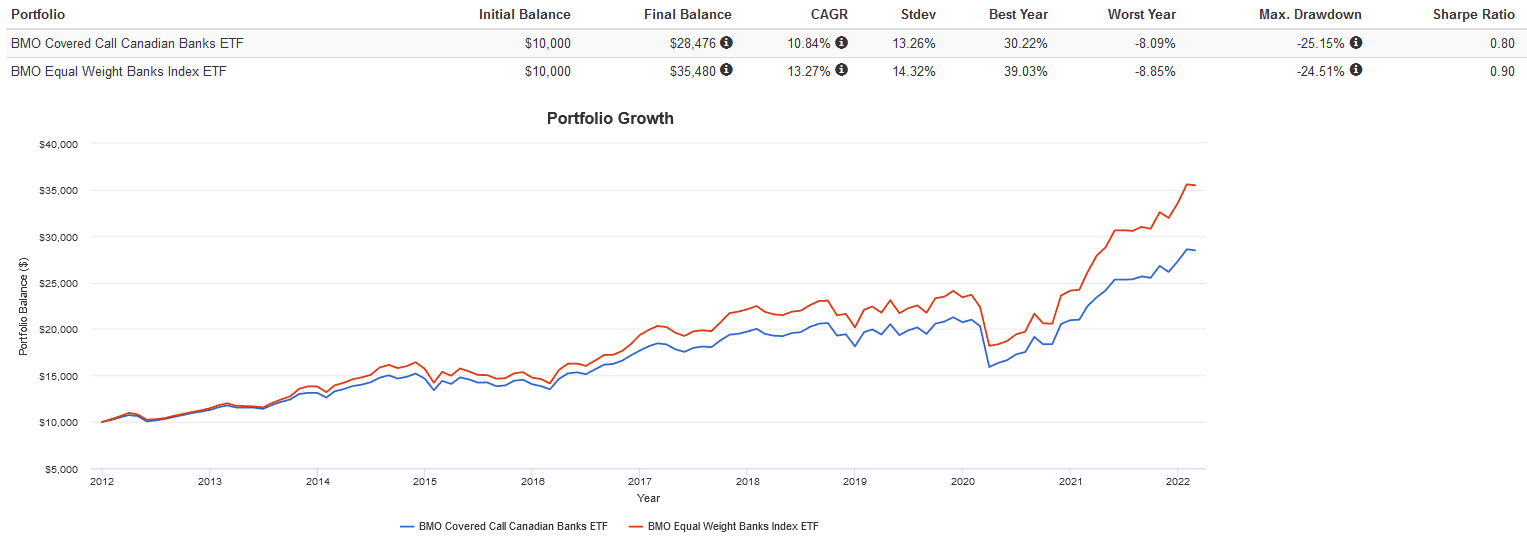

I plotted a backtest with all distributions invested for two ETFs: BMO Canadian High Dividend Covered Call ETF (TSX:ZWB) and BMO Equal Weights Bank Index ETF (TSX:ZEB). Both hold Canadian Big 6 Banks, but ZWC has a covered call overlay.

There’s no contest here. Even though ZWB has a higher yield of 5.80% versus 3.46%, it underperformed in terms of total return, volatility, best year, and risk-adjusted returns. ZWB had the same downside risk as ZEB, but with its upside capped. This also comes at a much higher management expense ratio of 0.72% versus 0.28%, which eats into your gains over a long time period.

The verdict? Avoid covered call ETFs, unless for some reason you desperately need high monthly income (which may be better met by a combination of preferred shares and corporate bonds anyway).