New investors often gravitate to large-cap, blue-chip Canadian and U.S. stocks. These includes companies like Royal Bank, Enbridge, Shopify, Apple, Microsoft, and Alphabet.

The reasons for this are numerous. Investors may be attracted to their stellar outperformance over the last decade, opting to bet on that continued growth. They may enjoy the juicy dividends that some of these stocks pay out. Or they might use many of the products and services they provide, deriving a feeling of familiarity and comfort from supporting their favourite company.

Even investors not stock picking and opting for a passive investment approach using index funds will still have the majority of their portfolios concentrated in large-cap stocks. This is because the majority of index funds are market cap weighted, with more holdings allocated to large-cap stocks.

What is a large-cap stock anyways?

I gave some examples of well-known Canadian and U.S. large cap stocks earlier, but the list doesn’t end there. The technical definition of a large-cap stock is one with a market capitalization (share price times outstanding share count) of more than $10 billion.

This definition encapsulates most of the stocks contained in well-known stock market indexes like the S&P 500, the S&P/TSX 60, the Dow Jones Industrial Average, and the NASDAQ 100. If you’re investing in these indexes, your portfolio is certainly large-cap heavy.

What about small-cap stocks?

There is another category of stocks on the opposite end of the spectrum called small-cap stocks. Small-cap stocks are those with a market capitalization of $300 million to $2 billion. Often, these are smaller up-and-coming companies.

Research by renowned investors Eugene Fama and Kenneth French (Fama-French) has shown that over long periods of time, small-cap stocks consistently outperform their large-cap counterparts. This is called the “size” risk factor, otherwise called “small-minus-big” (SmB).

The reasons for this are varied and worth an article on their own. In general, we can say that because small-cap stocks are more volatile (and thus riskier), investors who buy then can expect higher returns as compensation. Moreover, when small-cap stocks rise, they tend to do so violently. Look at Tesla before it entered the S&P 500 as an example.

Small- vs. large-cap investing

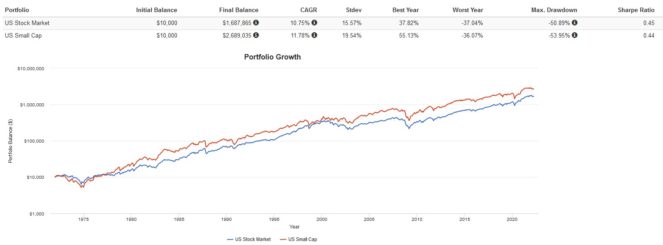

Many new investors expect large-cap stocks to outperform small-cap stocks, but the reality is that since 1971, the opposite has been true. Take a look at this backtest plotting the total U.S. stock market vs. U.S. small-cap stocks.

The above backtest contains trailing returns, which are influenced by the particular start date chosen. To remedy that I’ve also included three-, five-, 10-, and 15-year rolling period backtests, which, again, show small caps winning handsomely.

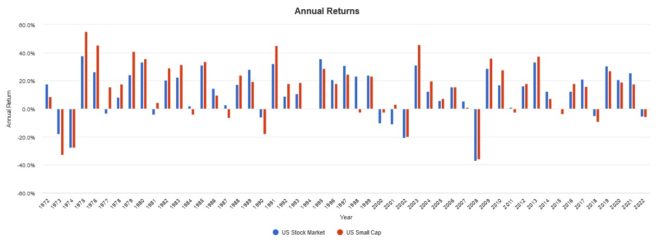

We can also examine the annual returns, which show small and large caps taking turns outperforming. Notably, most of the large-cap outperformance came in recent years after the 2008 Great Financial Crisis with the rise of the tech sector.

The Foolish takeaway

There’s nothing wrong with holding an index fund and accepting the market cap weights it assigns you. By doing so, you’re acknowledging that you’re willing to accept the market’s returns, which already puts you in a better position than most stock pickers.

However, if you have a long time horizon and can stomach more volatility for the chance at beating the market, tilting your portfolio by overweighting small-cap stocks could be a viable strategy. Keep in mind that for this strategy to work, you have to have discipline and stick to it, even when small caps underperform.