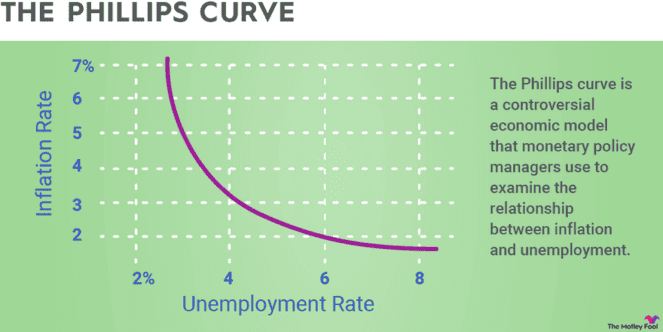

The Phillips curve is a controversial economic model that monetary policy managers use to examine the relationship between inflation and unemployment. The model shows that wage inflation can lead to reduced unemployment, at least over the short term.

What is the Phillips curve?

The Phillips curve is a model that attempts to show the relationship between inflation and unemployment. Central bankers who are responsible for policies creating maximum sustainable unemployment and low inflation have used it for forecasts.

The idea behind the Phillips curve is simple: As employment falls, there’s an increase in demand for workers. Wages will go up since employers need to pay more to attract workers. When wages go up, inflation follows. The model suggests that the inverse is true: In times of higher unemployment, there’s less need for companies to pay premium wages, so costs — and inflation — are tamped down.

The Phillips curve, named after a New Zealand economist who wrote about the relationship in the U.K. in 1958, isn’t considered to be foolproof. By 2011, at least a half-dozen Nobel Prizes have been given to economists who have criticized it. The most common criticism stems from the experience of the early 1970s, when many economies were bedeviled by stagflation, or an economic cycle marked by high unemployment rates and rising inflation.

Many economists now believe the Phillips curve is a useful tool, but only in the short term.

Why is the Phillips curve important?

Before the 1970s, policymakers used the Phillips curve to monitor the money supply and control inflation. If unemployment rose above a target rate, central bankers such as the Bank of Canada would lower interest rates to encourage more spending and hiring. If unemployment fell, bankers could increase rates to keep inflation under control.

Actions by the Bank of Canada have major implications for your investments. When inflation is high, for example, it may cost companies more to borrow when the central bankers boost interest rates, and their wage costs may have to rise to ensure members of a well-trained workforce don’t seek greener pastures.

And, when unemployment is low, some investments — such as simple bank accounts or guaranteed investment certificates (GICs) — may be less attractive. As we saw during the COVID-19 pandemic, low unemployment can present its own set of problems for corporations since supply chain issues prevent them from acquiring goods and materials in a timely manner.

Using the Phillips curve

The Phillips curve features the unemployment rate on the horizontal axis and the inflation rate on the vertical axis. A straight vertical line is drawn on the horizontal axis for the natural unemployment rate.

If the economy is in a recession, the unemployment rate will be higher than the natural unemployment rate, and the Phillips curve will be to the right of the straight vertical line. As the economy recovers, the curve will move farther to the right if a higher level of inflation is predicted.

The Phillips curve can be useful information for investors, but only to a degree. It has gone through almost two decades of flattening, with unemployment rising and falling while inflation remained static.

One of its key shortcomings is the assumption that inflation is only associated with a single country’s unemployment rate — a concept that has become outdated in a globalized economy. Yet it’s worth noting that when Canadian inflation was rising sharply in late 2022 as the COVID-19 pandemic waned, the nation’s unemployment rate decreased in January 2023 to its lowest level in over fifty years.

Example of the Phillips curve

Let’s look at a basic example of the Phillips curve. Say our inflation rate is 6%, and our natural unemployment rate is 4%. We can draw a vertical line from the horizontal (unemployment) axis and a horizontal line from the vertical (inflation) axis.

The Bank of Canada might normally respond to this by raising interest rates to keep inflation from climbing higher, and that approach might work. But in this example — where inflation is tamed by the BoC and falls to 2% — unemployment rises to 7% because there’s not as much demand for workers to produce more goods and services.

Again, there’s no absolute guarantee that the economy will behave in ways that models show. As we’ve all learned, the economy has ways of surprising us. And although the Phillips curve may be a useful tool for central bankers, investors should keep in mind that it’s a generalization. Inflation will frequently lead to lower unemployment, but only over the short term. As always, investors are best served by a buy-and-hold strategy that doesn’t try to time the market or make short-term predictions about the future of the economy.